4. California Resettlement

In 1956, Hou Beiren and his family were granted refugee status and resettled in the United States. After the passing of the Refugee Relief Act in 1953, the United States Congress had given permission for 5,000 visas to be granted to refugees in Asia, with 2,000 specifically reserved for Chinese with passports endorsed by the Republic of China (ROC).1 Known as the Far East Refugee Program (FERP) of the United States Escapee Program, or more simply as the Far East Refugee Program, this initiative focused on the resettlement of a small number of “bona-fide Chinese political refugees who are identified as being in groups or categories having special political or psychological significance.”2

Hou had been offered resettlement during the initial round in 1953 but declined. He was again offered resettlement in 1956 and, fearing it might not be extended again, decided this time to accept.3 In addition to his political significance as a university educated member of the nationalist elite, Hou’s role as an artist and writer ensured that he stood out from the ordinary mass of poorly educated refugees in mid-1950s Hong Kong, and that he aligned with the positive propaganda goals Dulles saw as being essential.4

In November 1956, now aged 39, Hou Beiren, with his wife and two young children, began a new life in Los Altos, in Santa Clara County, California. This region had long established ethnic Chinese communities. In the aftermath of the nationalist retreat to Taiwan from mainland China in 1949, growing numbers of professional, educated and skilled Chinese expatriates and exiles began to relocate to this region from Taiwan and Hong Kong. Hou came to know many of the other nationalist exiles who settled in the region, some of them quite prominent, such as He Fengshan (1901–97), a former Guomindang diplomat who had served in Austria.5

The California in which Hou Beiren found himself during the mid to late 1950s was a complex and at times hostile place for ethnic Chinese.6 The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, prohibiting immigration to the United States by Chinese labourers, had only recently been repealed by the Magnuson Act of 1943.7 The Magnuson Act also made Chinese citizens eligible for United States citizenship, but only gave China an annual immigration quota of 105.8

Shortly after arriving in California, Hou got to know the painter Zhang Shuyi (1901–57) when Hou’s wife began to work in Zhang’s studio in Piedmont, located near Oakland.9 Zhang had arrived in the United States in 1941 to promote Sino-American cultural diplomacy, and he had toured America extensively, holding numerous exhibitions and conducting public demonstrations of his painting, which attracted great public interest and press coverage, arguably becoming the best-known Chinese painter in America at that time.

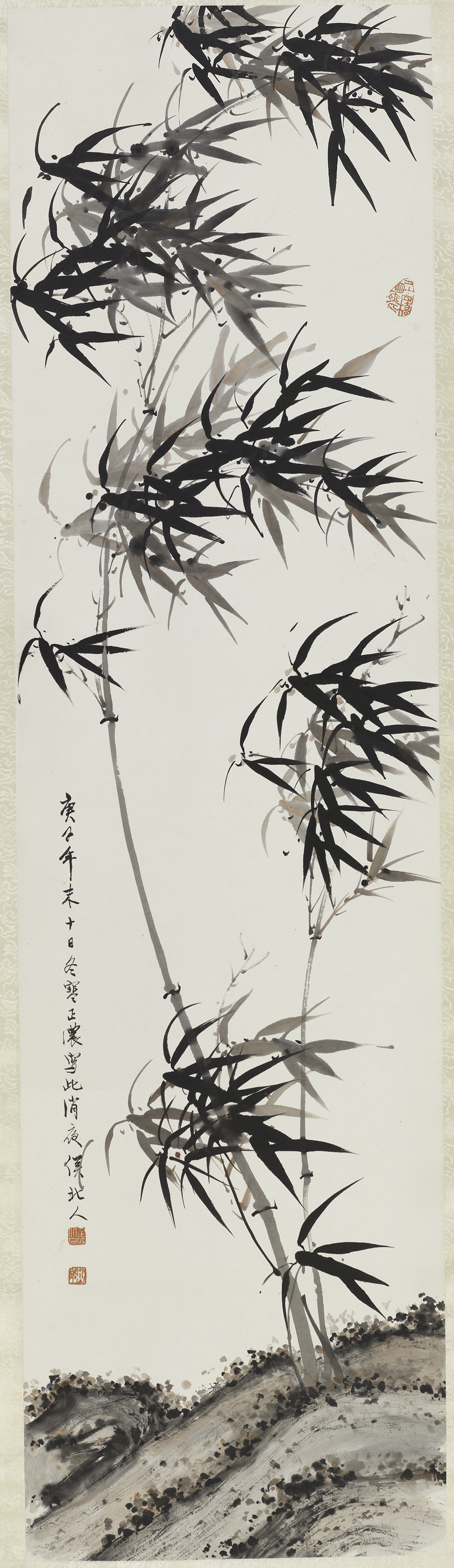

With only limited English, Hou, now known as Paul Hau or Paul P.J. Hau, was faced with few immediate or attractive options for employment and chose to rely on what were now, in this completely new cultural context, his most saleable skills: selling and teaching Chinese ink painting. He began teaching Chinese painting and calligraphy at the Palo Alto Art Club (later the Pacific Art League) in 1957.10 Soon after finding himself in California he began holding exhibitions of his work, which sold well, and it was during this period that his identity as a painter and art teacher became fully established.11

By 1973, an article in the West Valley Weekend reported that Hou had exhibited in “major galleries throughout the world in China, Japan, Vienna, Austria, New York and at the de Young Museum in San Francisco.”12 He had solo shows at the University of Santa Clara’s de Saisset Museum in 1959 and 1962, at San Francisco’s de Young Museum in 1963, the New Orleans Art Museum in 1964, the San Jose Museum of Art in 1980 and the San Francisco Chinese Culture Centre in 1988.13 By the early 1960s, Hou’s exhibitions had been successful enough to allow him to purchase a home in Palo Alto, which he later named Old Apricot Villa (Laoxing Tang), around which he built a traditional Chinese style garden.

Notes

-

Oyen 2014: 196. ↩︎

-

Hsu 2015: 172. The program was modelled on the Truman administration’s (1945–53) United States Escapee Program, a relief initiative set up in 1952 for Communist Bloc refugees in Europe, though in Hong Kong the State Department merely coordinated and supplemented the assistance given to escapees by voluntary agencies, who in turn provided food, shelter, health care and vocational and language training for refugees. See Davis 1998: 136. ↩︎

-

Johnson 2016: 9. ↩︎

-

Oyen 2014: 196. ↩︎

-

These are listed as: 社會學史綱 Shehui xueshi gang (A Survey of Sociology); and a collection of writings entitled 畫與家 Hua yu Jia (Painting and Artists), again published under the pseudonym of Duanmu Qing: 端木靑. 畫與家.香港: 高原出版社, 1958. See also Hou Beiren Meishuguan 2014, vol. 2: 234. A newspaper clipping from the early 1960s describes Hou as having been an editor for the Freedom Press, and/or a journal entitled Free Front while in Hong Kong. See Hou Beiren Meishuguan 2017: 158; Johnson 2016: 9. On making a living in Hong Kong, see Yu 1986: 60. ↩︎

-

The lack of diplomatic relations between the U.S. and the PRC meant that immigration from mainland China had ceased and would remain so until 1979, when relations between the two were again normalised. ↩︎

-

Hou Beiren meishuguan 2017: 42. See Yu 1986 for multiple accounts of mainland Chinese and former nationalists who made successful lives here. ↩︎

-

Some examples of legislation with restrictions applied specifically to Asian immigrants and immigration include the Alien Land Law of 1913; the Johnson-Reid Act, also known as the Immigration Act of 1924; and the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934. ↩︎

-

Also known as the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act. ↩︎

-

Johnson 2016: 9. ↩︎

-

Nanhai Art 2016: 88. Hou Beiren meishuguan 2017: 142. ↩︎

-

Hou Beiren meishuguan 2017: 111–112; 151–156; 158; 162. Press reports from the late 1950s and early 1960s reproduced in this volume typically describe Hou’s painting style as being in “the tradition of Sung and Yuan dynasties of the 9th to 13th centuries.” ↩︎

-

Hou Beiren meishuguan 2017: 149. The M. H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park is part of a group of museums known as the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. ↩︎