6. Twentieth-Century Revival

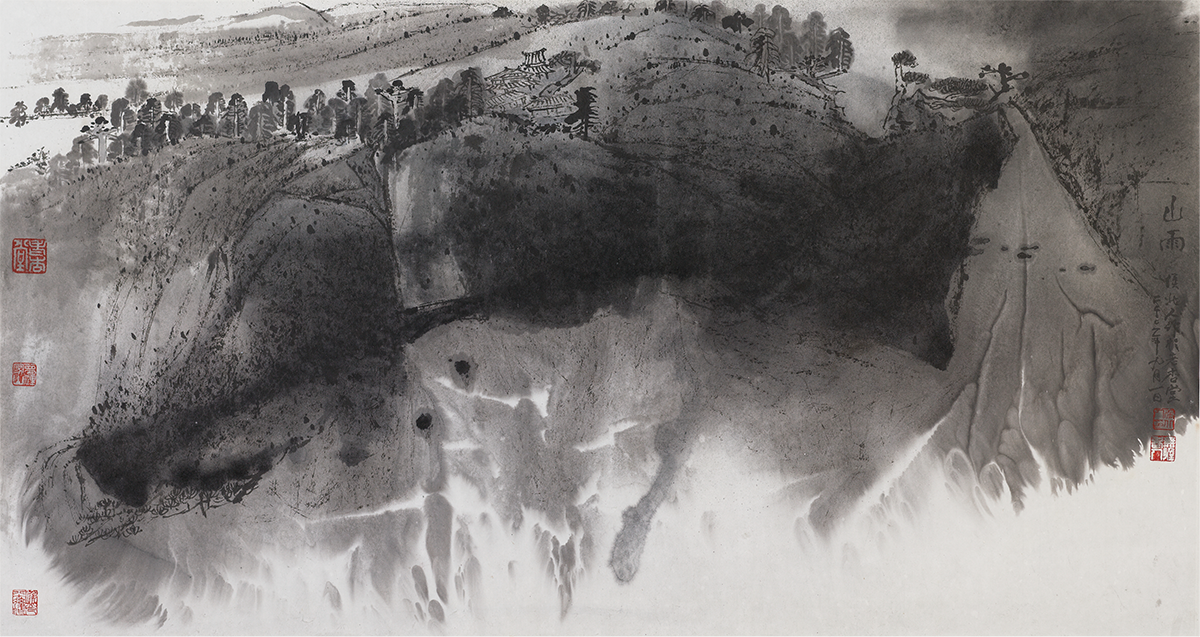

The process of splashed ink landscape painting (pomo shanshui) involves a seemingly unrestrained and arbitrary approach to the application of varying dilutions of ink to paper or silk through a combination of various intensities of spontaneous, semi-intentional and accidental processes that include splattering, dipping and smearing, often using larger brushes heavily loaded with ink that results in an element of chance, to which more deliberate textured brushstrokes can be added in the final stage of the painting so as to transform the gestural abstraction of ink with figures, trees, buildings, bridges and other figurative elements into a representational depiction.

Implied within the pairing of brush and ink (bimo) is the primacy of the brushstroke, for which there exists a rich and detailed terminological glossary in Chinese painting. This dichotomous push-pull interplay between brush and ink remains evident in Hou Beiren’s paintings, especially his later works, where a constant tension plays out between the figuration of the brush and the abstraction of ink. The aesthetic of splashed ink completely dominates in Hou’s paintings, while the brushstroke is never entirely surrendered or discarded. His brush remains a potently expressive signifier and index of hard-won proficiency within the culturally privileged inheritance of ink painting and calligraphy.

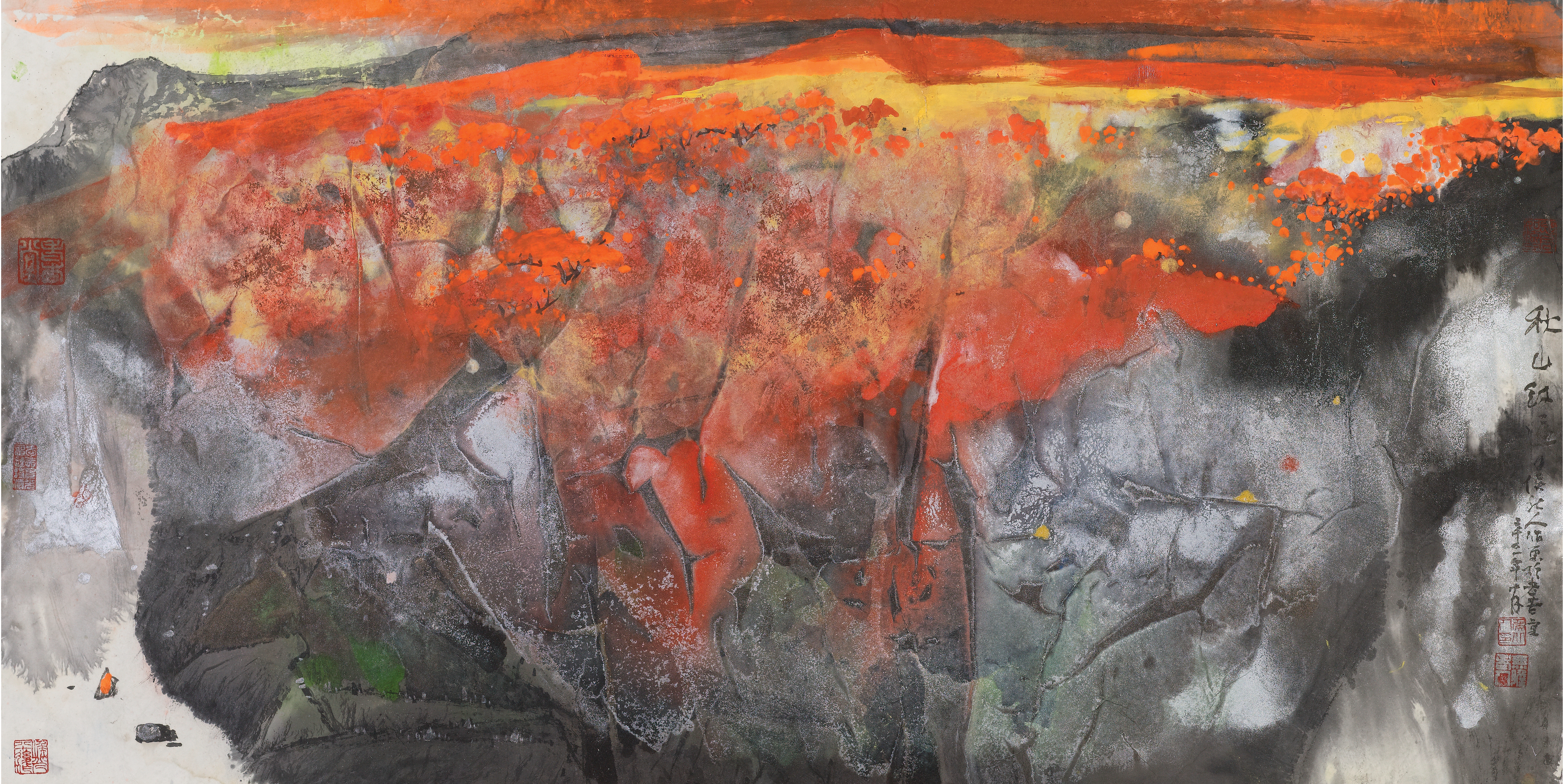

So too, the constant flux and interplay in Hou’s late work between the underlying layers of shadowy black ink and vibrant overlays of splashed colour create a kaleidoscopic fusion of landscape, cloud, mist and water recalling the primordial chaos (hundun) of early Daoist thought. Incipient matter swirls indeterminately, hovering on the point of coalescing into comprehensible form, with Hou’s paintings fluidly alternating between subject and medium in a manner recalling Impressionist painting.

The use of splashed ink occurred only occasionally after the Song period in China and remained largely overlooked within the mainstream of Chinese painting until its revival by Zhang Daqian in Europe in 1956.1 By the mid-1950s, the decline of Zhang’s eyesight due to diabetic retinopathy became one of the factors prompting him to begin experimenting with the technique, since his deteriorating sight no longer permitted him to engage in fine line work.2 It seems likely that, despite claims by Zhang that these compositions were predicated upon well-known Tang and Song dynasty precedents, they were more likely a response to his contact with Western art, most notably Abstract Expressionism in America and the associated non-objective and experiential art movements that dominated the post-World War II art world, such as Gutai in Japan, Fifth Moon Art Group in Taiwan, Tachisme, COBRA and Art Informel in Europe. When Zhang began experimenting with splashed ink painting while visiting Paris in 1956, it is likely that his interest in splashed ink was to some degree motivated by a concern with retrieving China’s artistic past.3

The addition of colour in his work began around 1960 and appears to be entirely Zhang’s own innovation, since while texts dating back to the Tang describe painters using splashed ink, none mentions the use of colour, and no examples of splashed ink painting including the use of colour survive prior to Zhang Daqian.4 Colour in his splashed ink painting was central to his compositions, which were built up with rich ink gradations, and not merely a secondary addition after the application of black ink.

Independently of Zhang, other leading artists also had begun experimenting with splashed ink. Zhu Qizhan (1892–1996) and Liu Haisu (1896–1994) both employed it to varying degrees. Liu Haisu remained in China and so appears to have heard about Zhang Daqian’s work indirectly, with news of his work filtering into the Mainland during the 1970s, when Liu began to employ splashed ink more extensively.5 In common with Liu Haisu, Zhu Qizhan was based in mainland China, but with the opening of China during the Reform and Opening Era (Gaige kaifang) of the 1980s, Zhu was able to travel overseas, and in one photograph, he and Hou Beiren are shown meeting with the American landscape photographer Ansel Adams (1902–84).